‘Crowd Control’

Wood, Concrete, Hinges

5 x 25 x 3.5 mts.

The aesthetics of risk control

Interview with Jasper Niens by Ingrid Commandeur.

Jasper Niens is one of the artists from Rotterdam to realise a project on location for The World of Witte de With. Niens (1980) graduated in 2003 from the AKI Academy in Enschede and has since then made ‘architectural installations’, as it’s called. He builds constructions in public spaces, but also works within the institutional context of galleries and art fairs. At the Art Forum Berlin 09 he presented Handicap Principle II for example, a large round, cylindrical aluminium form, that could be moved with an ingenious revolving mechanism. Niens consciously offered a strange experience instead of saleable art. Visitors could enter the space through a door with the risk that this entrance would be blocked by others through the revolving motion of the cylinder. Such a construction might be allowed at an art fair, but would that still be the case in our public spaces that are closed off by security measures? These are relevant questions to Jasper Niens. His work is continuously occupied with the direct confrontation with the viewer and the provocation of unwritten conventions with regards to the use of public and semi-public spaces. And this is often accompanied by a struggle. My conversation with Jasper Niens was going to begin with a look at his practice in the past five years, but we fell head-long into the present. Niens has just heard that his project proposal for the Festival The World of Witte de With has been turned down: “The Permits Dept. handed it onto the Council’s Security Dept., which in the end gave it a ‘no go’. I had expected this in a way, because the work concerns security and regulations.”

Ingrid Commandeur: ‘Could you comment any further? How was the work going to relate to the context of Witte de Withstraat and its surroundings?’

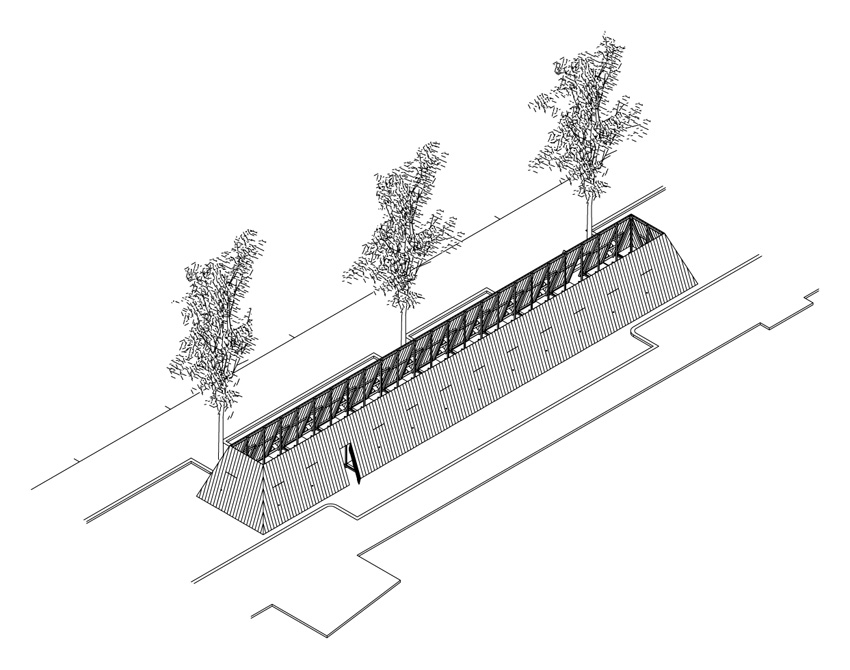

Jasper Niens: ‘To answer this question I’d like to first go back to another project which I think of as its precursor. In 2009, I was invited to take part in a sculpture route at Minervalaan in South Amsterdam. The location was a beautiful lane with various trees and villas surrounding it, with a strip of public space in the middle. My work for this sculpture route simply consisted of framing part of this public space with a 16x17metre wooden wall. There were doors in that wall that you could lock from the inside, so passers-by could claim the space as theirs. The project was embraced and approved by the organisation. However, after a few weeks, there was some unrest: people living in the area had vandalised the work. People were afraid local young rascals would assemble there. The work had to be repaired, but was instead broken down, while it was supposed to have stayed there for three months. I am still involved in a court case with the organisation of the art route concerning this matter.’

Do you think of the after effects of such a project and the court case as part of the art work?

‘Yes, in this case I do. It’s about the story as a whole: a proposal for a work that is chosen and approved by the inhabitants themselves, while after its realisation, its treatment changes from embracing it to making it one’s enemy. It lays bare all sorts of things about the tension and controversy that such a simple work in the public space can evoke. It also says something about the harsh reality surrounding life as an artist. If they lose the court case they won’t feel a thing, if I lose I’m bankrupt.’

How do we go from that to the Witte de Withstraat, where they’re not exactly planning a chic sculpture route?

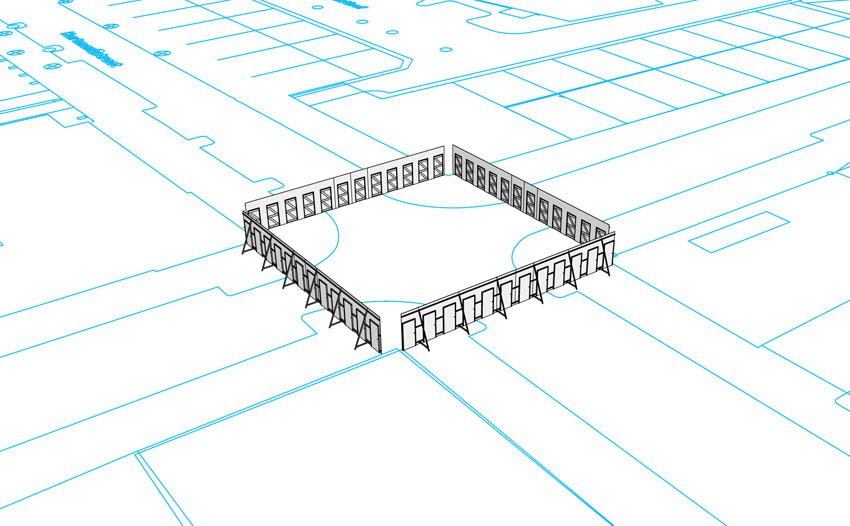

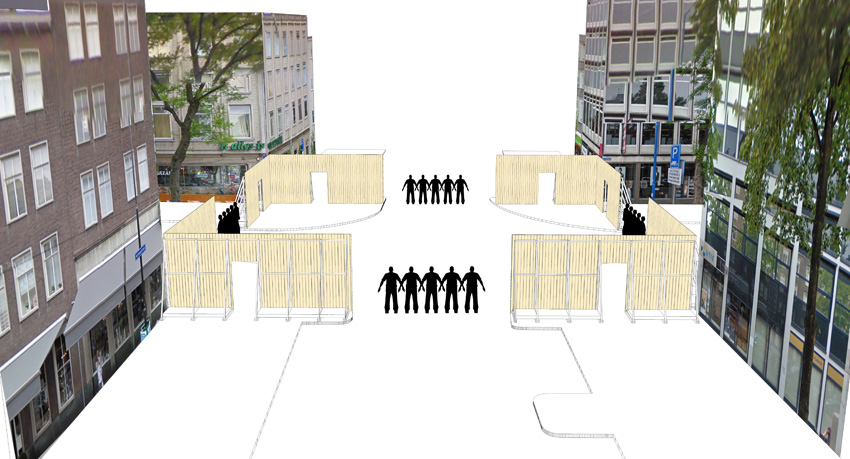

‘The plan I’d handed in for the festival is very similar: I wanted to cordon off the crossing between Witte de Withstraat and Hartmanstraat with a fence that ran from façade to façade. With twelve doors on each side, in this case, that could also be locked on the inside. This didn’t concern the claiming of space, but the fact that the public themselves decide the route across the crossing. You can stand on the crossing, without being limited by the rules people normally have to abide by. This work, to me, is also about how people react together to the codes belonging to a certain space and the public can change those.’

Before Duisburg this might have seemed a relatively ‘harmless’ project proposal, now, though, the placing of a deliberate obstruction in front of the visitors to a festival may be interpreted as a quite emotionally charged and provocative gesture.

“Yes, that’s right. The Monday after the news concerning the disaster at the Love Parade in Duisburg, I had to send the council an update about my work, with new drawings and details about how to open up the street to the fire brigade. With what had just happened in Duisburg, I suddenly found it hard to solve that. Duisburg has not changed my work, naturally, but I suddenly found it hard to justify. While the work was designed with a double calamity exit route: the public can exit the doors and the fire brigade has a separate exit built into the structure, which can be thrown open quickly. Twelve openings are more than enough to escape through for the audience. The work complies with the regulations, but, nevertheless, they won’t allow it, especially now. That, undoubtedly, has to do with what happened in the Hook of Holland and more recently in Duisburg.”

Perhaps that’s justified. But it doesn’t make your work any less interesting: it concerns people’s behaviour in public spaces, risk control and ‘the emotions’ this evokes in people. A controversy about an incident in a public space in Europe has a direct bearing on how people see your work. A simple wooden wall suddenly becomes an image of terror.

“That’s right, even though, for my own part, I’m not scared of anything. The way in which people relate to each other in the work isn’t emotionally charged. The space people have between each other is much larger than the sixty centimetres described as the zone of intimacy not be crossed at public events.”

How has your work developed in recent years?

‘At first, I think my work was more concerned with owning space: public space versus private space. Some years ago that was actually in issue in society. In recent years I’ve noticed my work is becoming more physical and radical. It’s more about how risk is experienced. My statement is that risks have become invisible in our present-day, urban environment and that this is a loss. My aim, therefore, is to make ‘dangerous’ architecture. That is quite difficult, because there isn’t much room for error: if a work evokes reactions that are too predictable, it falls flat on its face. I also think the chosen form and the aesthetics concerned are vital.’

Dangerous architecture? I can imagine that when you wrote that down the Security Dept. thought: that’s not something we want to participate in.

‘Then let me expand on that. Clearly, I am not looking for radicalism in literal insecurity. It concerns a subtle, stifling feeling that architecture can evoke and the realisation that when you relate to a space in a natural way, without everything being boxed up, regulated or marked with signposts, you will be more aware of the dangers. That is what I want to express with my work: I make risks visible that are already there. Security systems also, in some way, make risks less visible.’

Is Duisburg an example of that?

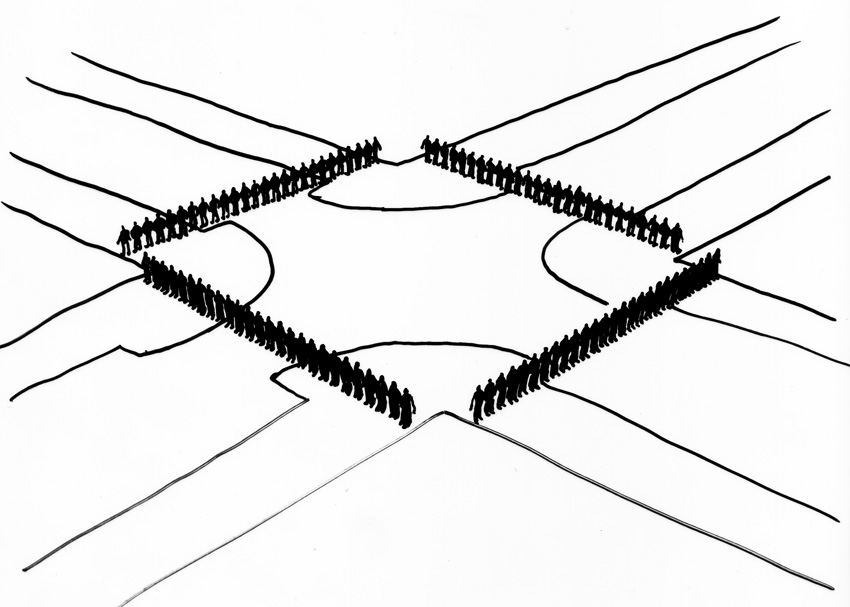

‘Yes, I think that in general more people tend to pass responsibility for risk assessment at mega-events onto the organisers, onto a higher authority in other words and not themselves. The visitors of the Love Parade weren’t in any way prepared for the fact that people’s reaction to space can suddenly switch to survival mode. The design for the crossing is also concerned with this, but let me emphasise it again: at a totally different level. I wanted to make a work about the masses that flock to a festival, about how systems are designs to control the masses and direct them towards a certain place, just with an entrance.’

What will happen now?

‘The organisation suggested we build the work somewhere else, but because concept and location are inextricably linked, that, to me, isn’t the solution. However, for quite some time I have been toying with the idea to experiment with a hybrid between an object and a performance. You can let groups of people form geometrical shapes that, similarly, form a coercive constellation that visitors will bump into, like a wall. Think, for example, of a cordon of security people, who walk down the street six rows deep in a set pattern. But at this point I don’t know whether that’s a new, valid inroad into this project and what it will entail. So, whatever happens, visitors will be surprised.’