2007

2007

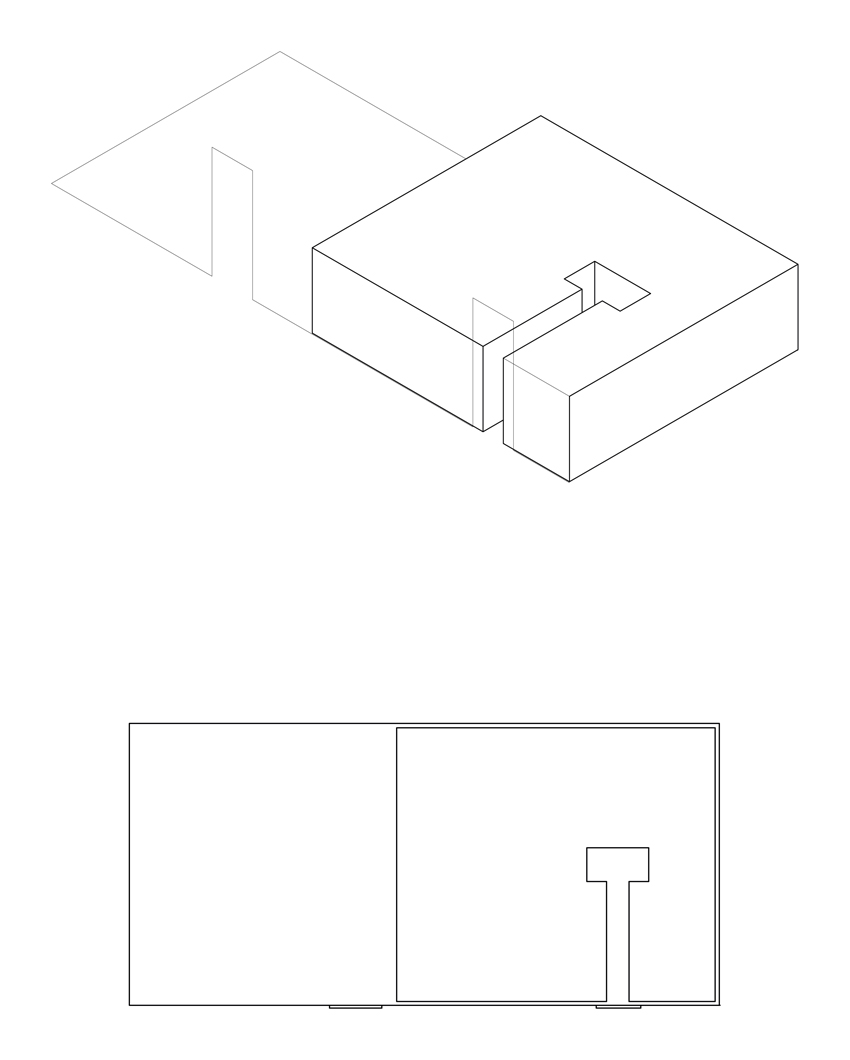

‘The Handicap Principle I’

5 x 4.5 x 1.5 mts. Wood, Wheels

Gallery West, The Hague

The Handicap Principle I

An essay by Philip Peters

“A sculpture”, Barnett Newman says, “is a thing which you trip over when you walk backwards to view a painting.” Of course, that was partly bantering, but it is also true in the sense that a sculpture, a work with three dimensions, is located in ‘our’ space and occupies a certain amount of it. That entails all kinds of possibilities for the work in order to engage with us which go further than the classical round sculpture which, whether on a pedestal or not, is intended to be walked round and viewed from various angles.

The Handicap Principle I by Jasper Niens concentrates on our functioning in a space. It consists of a large square wooden block with wheels underneath and it fills the room in its width, you cannot get past it. When you enter the gallery, you cannot go any further than the front of the room. The wooden block stops you from going any further, it is an obstacle. In the middle of the block there is a narrow ‘little corridor’ (more a kind of groove in the wood with just enough room for one person) which ends in a short T division. The person who wants to get to the other side of the room has to depend on someone else for this who is already there and is willing to push the block towards him (which is not easy) until the ‘little corridor’ is positioned at the height of the entrance door to the room. Then he can enter and then therefore become a part of or at least a participant in the work and push the block backwards again so that he can get out of it again. The same process also applies in reverse: if the block has ended up at the front of the room, people at the back are dependent on someone at the front being willing to push the colossus backwards, in order to leave the gallery. Someone who is not strong enough to push the block completely from one end of the room to the other, is out of luck: he is imprisoned in the work of art until someone else can free him.

Anyone who cannot move freely is handicapped and in this case every visitor is saddled with the same handicap: for his functioning he is dependent in the first place on the presence of someone at the other end of the room and also at that person’s discretion: after all, that person could also decide not to oblige him, in which case he will never come any further than the front of the room. The same applies the other way round.

This work is both interactive and authoritative at the same time. It is interactive because it is activated by people in order to be able to function and it is authoritative because it forces those people into certain actions. In a certain sense, you could call this a ‘social sculpture’, not in the utopistic sense which this term had for Beuys and his disciples, but precisely in a confrontational way: it prescribes behaviour, it determines what you have to do to get from A to B.

The work makes it clear that we are social beings and function within networks, whether we like it or not: we are dependant on each other; we accept this in an economical sense (you give the baker some money and you get a loaf of bread in exchange for it) without paying any attention to it. However, with regard to relationships with people, we usually think in a different way: partly, in terms of regulations, customs and protocol, partly in terms of emotion, attraction and rejection. Nevertheless, these relationships can also be expressed perfectly in economic terms: you invest in a relationship which then has to yield a return; if the return disappears, then the best option is to terminate the investment – which does not have to mean that this always happens either; in a relational context, there are reckless and ineffective investors just the same as on the stock exchange trading floor.

In this way, this work becomes a neutral instrument in itself – a physical obstacle does not automatically have a moral character, it is just a thing which is in the way – in order to chart or in any case evoke or suggest human behaviour. In this case, you can imagine that people will follow the rules of the game by definition – just as people also adhere to rules and regulations in a broader sense, more than they do not adhere to them – and allow each other to go from A to B and back again. This still does not explain the motives for that: the first thought is that people will obviously be solidary and that someone who has been helped from A to B himself, will also do that for someone else. However, it is also the case that anyone who does not adhere to these types of unwritten rules will not behave in the same way en plein public – therefore, in the gallery, people will help each other, but that does not say much about other circumstances, so no conclusions can be drawn from this. That is not necessary either – art is not science, or behavioural science and therefore this work is only a reason for behaviour and, what is at least as important, a reason to reflect upon behaviour and motivation. This takes the work from one area of meaning – the literal circumstances – back again to where it also and primarily belongs, as art: to the realm of the imagination.